Summer

ends with David Lynch’s “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me,” Nicolas Cage

unraveling in “Honeymoon in Vegas,” and Edward Furlong screeching through “Pet

Sematary II.”

Twin

Peaks: Fire Walk with Me

Nutshell:

The brutal murder of Teresa Banks brings Agent Desmond (Chris Isaak) and Agent

Stanley (Kiefer Sutherland) in to investigate the crime, coming across evidence

of a serial killer employing specific targets and leaving cryptic clues. Years

later, we find Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) suffering in Twin Peaks, using drugs

and prostitution to numb her flattened soul, fearful of Bob (Frank Silva), the

demon who visits her bed and torments her dreams. Caught between lovers while

trying to keep friend Donna (Moira Kelly) off the scent of her corruption,

Laura inches closer to dark revelations about her unhinged father, Leland (Ray

Wise), terrified that the goodness of the universe has left her behind, making

the destructive days before her slaughter agonizing.

1992:

When “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me” was released, I wasn’t fanatical about the

television series that inspired the feature. “Twin Peaks” had already finished

its run, and while its pop culture dominance was thrilling to watch (spawning

endless magazine covers, entertainment show discussions, and merchandise), it

didn’t rub off on me until later, where hindsight assisted in a deep

appreciation of the David Lynch/Mark Frost creation. What was so appealing

about the movie was its timing, released a year after the show was canceled and

largely dismissed by the tastemakers at Cannes, creeping into view at the very

moment nobody wanted to see it. That level of ballsiness or delusion doesn’t

pop up every day, leaving me breathless to see the picture and immerse myself

in this decidedly R-rated take on “Twin Peaks.” With Frost melted away, Lynch was

left on his own to molest his creation however he saw fit. Awesome.

At

this point, I had already viewed “Blue Velvet” and “Wild at Heart” through home

video opportunities, creating awareness of Lynch’s wily art-school ways from a

controlled distance. Needless to say, a theatrical powwow with “Fire Walk with

Me” was like taking a sledgehammer to the face, smacked with a type of

surrealism and abstraction I had no education in. Its ethereal and demonic

sight and sounds (the nightmarish sound design on this baby should’ve collected

an Oscar) messed with me, supplying an unfiltered cinematic journey into the

unknown, populated with television actors, movie stars, and music legends,

while interpretive dance, ghoulish masks, and the regurgitation of creamed corn

filled the screen, generating waves of delicious unease. “Fire Walk with Me”

was genuinely overwhelming, feeling like Kamala the Ugandan Giant was sitting

on my chest during the initial viewing, while Kyuss played a greatest hits set

on my gums.

It

was amazing.

“Fire

Walk with Me” was crippling, but in a beautiful manner, altering my filmgoing

DNA while triggering a mini-obsession with the “Twin Peaks” universe, which, to

my delight, was readily accessible in pop culture bargain bins everywhere. I

couldn’t detail movie particulars to an outsider, but Lynch’s dark magic made

sense in the moment, leaving a football field of interpretational space behind

for good measure, asking fans to wade through its black-tar plot, screaming

fits, and angelic sightings. The feature’s relentless obscurity was a sleeve of

Fig Newtons, and I happily gobbled away until crumbs remained, despite my

general distaste for blurred big screen math. Lynch lost his mind and I was

right there to inspect the wreckage, making the picture a true event with its

potentially career-killing directorial attitude. “Fire Walk with Me” was

promoted as a prequel to “Twin Peaks,” but it was actually Excalibur pushed

through the heart of a phenomenon, leaving the faithful to grieve, while

newcomers were left baffled, or in my case, ravenous for more.

“Fire

Walk with Me” also brought Moira Kelly back to the screen, an actress I was

developing a bit of a crush on at the time. Talking over the Donna Hayward role

previously played by Lara Flynn Boyle, Kelly was an unusual performer (best

known for her work in “The Cutting Edge”) with a disarming commitment to

emotional expression. I was quite taken with her full-bodied reactions to the

tiniest of dramatic encounters and her planet-sized eyes. She was an exciting,

classic screen presence in an era of grungy, sulky actresses. It was fantastic

to see Kelly folded into the Lynch extravaganza, though there was little for

her to do. Still, adding a familiar face worked in the film’s favor, keeping

“Fire Walk with Me” minutely accessible.

“Fire

Walk with Me” was my favorite movie of 1992. Top of the pops all the way. I

loved the madness in a profound way, making me a firm believer in Lynch’s caffeinated

voodoo. With this filmmaker, it doesn’t have to make sense, it should simply

convince. And “Fire Walk with Me” was spellbinding in its insane approach to

the mysteries of “Twin Peaks,” the soulfulness of the characters, and its

delirious, borderline suffocating presentation. Wowza.

2012:

The last two decades have revealed a great deal of animosity toward “Fire Walk

with Me.” It’s an understandable divide of opinion over an indescribable

picture, with some taking the viewing experience as an invitation to solve a

puzzle, while others simply throw their hands up in disgust. If I were a

betting man, I’d say this is exactly how Lynch loves to live his life, with his

“Twin Peaks” return a rich opportunity to indulge habits and experiment

further, risking the alienation of casual franchise fans. Love it or hate it,

“Fire Walk with Me” is stunning purging of abstraction and a steadfastly

demonic movie, still retaining much of its grip two decades later.

Of

course, gaps in the narrative that were tolerated before are quite obvious now.

Famous are the film’s deleted scenes, which have never seen the light of day.

“Fire Walk with Me” was reportedly a much longer movie at one point, and the

end product reflects an editorial pressure to push an elephant through a hula

hoop. Pieces are missing, subplots are lopped off in a crude manner, and most of

the television cast members are rudely reduced to cameos, a few (including

Madchen Amick and Peggy Lipton) are not even offered customary close-ups. Lynch

spackles the gaps with oddity and infestations of “Twin Peaks” red room

mythology, but it’s easier to spot the edits and the general confusion of

assembly. The first-time viewing is so devastating, so haunting, that making

sense of “Fire Walk with Me” is impossible. Subsequent trips to Hell highlight

the stitches.

Not

that I’m complaining about hiccups in a film as dynamic as this. After all,

Lynch is especially gifted with nonsensical material, turning messes into

hypnotic cinema, and “Fire Walk with Me” continues that tradition. It’s a scary

movie with flagrant goofballery and a pleasingly knotted soundtrack, also

making time to revel in perversion and self-destruction, instantly making it the

least liked feature in the history of the Red Hat Society. The effort retains firepower,

bewildering with its brain-melting mysteries, symbolism, and general “Twin

Peaks” outrageousness. Those who’ve devoted their free time to cracking Lynch’s

code have my deepest respect. I’ve seen the film on numerous occasions, and I

still don’t have a clue what’s actually happening beyond the basic questions of

the story. Green rings? Coded police messages in the form of a brightly

decorated female mime? Creamed corn as a manifestation for pain and sorrow?

It’s spectacular to watch, but I don’t have the patience to break the monolith

down into digestible nuggets. I prefer to consume my Lynch as quickly as

possible, embracing the inevitable confusion.

Thankfully,

Sheryl Lee’s convulsing performance grounds the viewing experience some,

helping outsiders grasp the danger and the recklessness of Laura Palmer. It’s

amazingly fearless work, gifting Lynch the whirlwind of emotions he needs to

help certain elements of chaos stick their landings. Ray Wise matches Lee well,

also diving into the deep end of madness with a severe take on the duality of

Leland. The two leads bring something special to the mix, embodying the macabre

and the mysterious with vibrancy and a clear communication of unavoidable doom.

Maybe one day we’ll get a chance to see the full vision of

“Fire Walk with Me.” At least something approaching an expansion of the film’s

scope, with a little more community participation. After all, who wouldn’t want

to mess around in this contaminated sandbox for as long as possible?

Honeymoon in Vegas

Nutshell:

A mild-mannered private detective with a love for gambling, Jack (Nicolas Cage)

promised his mother on her deathbed that he would never marry. Enjoying a

relationship with schoolteacher Betsy (Sarah Jessica Parker), Jack has evaded

her pleas for a marital union for years. However, Betsy is ready to exit the

relationship, prompting Jack to whisk her away to Las Vegas for a quickie

ceremony. Staying in the same hotel is Tommy (James Caan), a feared mobster who

sees a resemblance between Betsy and his beloved dead wife. Rigging a secretive

poker game to push Jack up against the wall, Tommy offers the reluctant groom a

chance to pay back his crippling debt by passing over Betsy for the weekend.

Upset with the situation, Betsy leaves with Tommy, who takes his fixation to

Hawaii with plans to talk her into marriage. Jack, growing restless with the

repayment scheme, tries desperately to make it to Hawaii as fast as possible

and prevent a relationship disaster. Tommy, aware of the potential intrusion,

does whatever he can to delay Jack, giving him time to sweet talk Betsy into

his bed.

1992: The Nicolas Cage we know today is an actor on the

verge of a career breakdown, accepting any job he can get his hands on to keep

the money train rolling along, no matter how harshly it reflects on his

professional reputation. In 1992, Cage barely had a professional reputation,

outside of being an oddball with occasional good taste in scripts. Perhaps

fearing he was in danger of being nudged out of Hollywood by those who couldn’t

compute his idiosyncrasy, Cage embarked on what he would refer to as his

“Sunshine Trilogy,” three features over two years that would come to redefine

his box office appeal and readjust his reputation for violent quirk.

“Honeymoon in Vegas” was the first of the trio (with

“Guarding Tess” and “It Could Happen To You” following), placing Cage in a traditional

romantic comedy lead role, as a dimwit trying to keep love alive in the face of

nonstop adversity. Although the actor had already worked his way through

numerous genres by this point, “Vegas” was a major step toward mainstream

acceptance, which, in a way, furthered Cage’s habitual need to throw the

industry off his scent.

I was a big fan of “Vegas,” finding the feature to be

hilarious and snappily paced, with Cage’s rascally performance a particular

pleasure in movie of many. While most of the media interest in the picture

gravitated toward the ridiculousness of the Flying Elvises (skydivers dressed

up as The King), Cage showed tremendous charisma in a tricky role, sustaining

his leading man appeal while stuffing numerous Cageisms in his front pockets

for later use. He was fun to watch, keeping the predictability of the production

down to a dull roar.

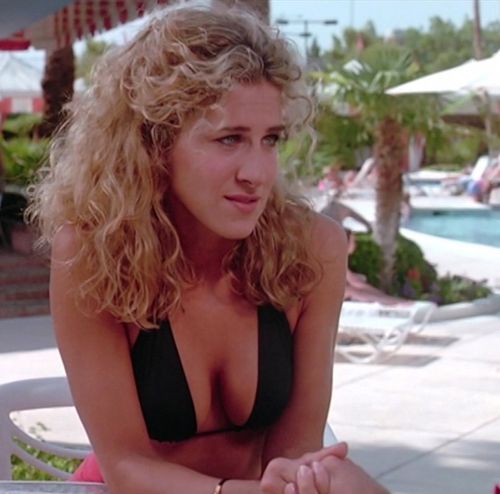

I guess 1992 was also a year to enjoy a Sarah Jessica Parker

performance. Man, how times have changed.

2012:

“Honeymoon in Vegas” feels a lot more insignificant these days, and I’m not

sure if it’s a reflection of my calloused attitude toward romantic comedies or

perhaps I was just enjoying the view back in 1992, without being fully

cognizant of the fluff. It remains terrific fun, with a charming simplicity

that often feels more like a chase picture than anything angling to be sweet,

following Jack as he soars across the world to retrieve his love, only to soar

right back when she begins to fall for Tommy’s tune. Director Andrew Bergman

sweats to maintain a manic vibe to the proceedings, but it’s a slack effort,

working to keep the three lead characters dimensional human beings while

preserving the material’s light farcical approach. I think the movie nearly

achieves a wonderful cruising altitude, yet seems determined to disrupt the

pacing with a few dud jokes, including an extended visit to a Hawaiian hippie

(played by Peter Boyle) that’s intentional in its purpose to delay Jack from

further travel on the island, yet offers no laughs. It’s a missed opportunity.

The

real curiosity about “Honeymoon in Vegas” these days is Cage, who’s feral and

free, all youthful and eager to try on the silk lining of a mainstream comedy.

He’s developed into a sour man sniffing around for paycheck gigs, but two

decades ago he was a searching actor, trying to entertain himself with quirks

and a busted volume knob, breathing life into a potentially dreary comedy. With

his wild, thinning hair and general look of disease, Cage’s interpretation of

Jack’s desperation is a total hoot, bravely unglamorous and consistently

agitated. Nowadays, these tics and whammies are expected, rehearsed into the

ground, so it’s highly entertaining to revisit Cage and his relatively new toys

of screen communication, spicing up “Honeymoon in Vegas” with manic attitude he

expresses so wonderfully.

Less

interesting is Caan, doing his umpteenth version of the irritated mobster/tough

guy routine, though this is possibly his most alert performance of the 1990s,

making a credible pass at seduction while visibly enjoying the Hawaiian

locations. Parker is less appealing, here during her sex kitten phase where the

studios tried to turn the awkward actress into a lustful female lead. Somewhat

whiny and stuck with a script that turns Betsy into a ghoul with rash marriage

plans, Parker is forgettable, caught between Caan’s screen comfort and Cage’s

impression of a chewed wad of Red Hots. You can tan, highlight, and bikini the

woman all you want, but it’s not going to make her memorable next to these

guys.

“Honeymoon in Vegas” keeps the giggles and the humiliations

for Jack coming, yet it’s the ending that’s the most successful element of the

feature. Bergman does a fantastic job escalating the picture to a position of

madness, requiring Jack to jump out of a

plane to save Betsy, accidentally joining the Flying Elvises on their

celebratory run over Las Vegas. Rare is the movie that actually knows how to

conclude in a satisfying manner, delivering spectacle and a little dollop of

romance while clinging to the traditional swatting of the baddies. It’s not a

particularly challenging climax, but it sends the effort off on a convincing

celebratory note, making the storytelling speed bumps feel less intrusive.

Pet

Sematary II

Nutshell:

After witnessing the electrocution death of his mother, beloved movie star

Renee (Darlanne Fluegal), teen Jeff (Edward Furlong) has joined his father,

veterinarian Chase (Anthony Edwards), in Ludlow, Maine, to help settle his

grief. Facing trouble from bully Clyde (Jared Rushton), Jeff befriends Drew

(Jason McGuire), an angry kid trapped under parental pressure applied by his

stepfather, town sheriff Gus (Clancy Brown). When his beloved dog is shot by

Gus, Drew takes the pooch to a special Native American burial ground that can

bring back the dead, who return with slightly demonic traits. When such

troublemaking escalates to the murder and reanimation of Gus, Jeff and Drew

discover the true nightmare of the “Pet Sematary,” along with its potential to

reunite Renee with the family she was so coldly removed from.

1992:

In 1989, I was invited by a friend to see “Pet Sematary” at a pre-release

screening held in an incredibly uncomfortable theater where an unruly crowd

gathered to watch the latest Stephen King adaptation, bubbling at the thought

of springtime frights distributed by an author who built an empire on sickening

events and troubling characterizations. While the picture played acceptably

with the amped crowd (it’s not a feature interested in a routine of cheap

thrills, but slow-burn madness), one scene sent the audience into a tizzy.

There’s a moment in the midsection of the movie where we meet Zelda, the

diseased sister of Rachel Creed (Denise Crosby), who’s imagined as a sickly

woman with demonic trimmings, contorted into a dreamscape monster meant to

cause great distress for Rachel and the viewer. Director Mary Lambert really

finds a clever way to bring Zelda to life, emphasizing bony body parts and dousing

the character in nightmare fuel, creating interest in a storytelling tangent

any other filmmaker would trim without hesitation.

Well,

the Zelda scene not only worked on this screening crowd, but practically

kick-started a few heart-attacks and ruined fresh underwear throughout the

theater. Once Zelda lunged toward the camera, these giddy ticketholders

collectively jumped sky high. Rarely have I seen an audience freak out in such

a manner, causing tremendous unrest, ruining any scenes that dared to follow

it. It was moviegoing beauty tattooed on my brain, while solidifying “Pet

Sematary” as a special picture in my eyes, capable of great disturbance and

creative acts of directorial evil. It also struck gold at the box office, leading

Paramount to do what studios do when they make a healthy profit.

They

ordered up a sequel. A “Two” for number two.

“Pet

Sematary Two” failed to match the original’s sheer nutso energy and enticing

creep, preferring punishing offerings of gore over a stable stream of suspense.

And to be perfectly honest, there were some expectations in place before the picture’s

release, despite a story heading in a new creative direction and the selection

of Edward Furlong for the lead role, then Hollywood’s latest it-kid for

productions in need of a whiny semi-actor with the face of a “Deadliest Catch”

veteran. The sequel welcomed the return of Lambert to the “Pet Sematary”

universe, but that didn’t seem to bring a pulsating evilness to the

proceedings. Instead, the follow-up died in a hurry, lacking the original’s

atmosphere, madness, and King-stained ghostly shenanigans. Paramount simply

wanted to build a fresh cash machine with a semi-remake, yet this time the

magic wasn’t there.

The

ghoulishness that was so intoxicating in “Pet Sematary” was depleted in the

sequel, replaced by a ho-hum effort that craved time with blood and guts, not

the unnerving stuff that has the potential to dive audiences crazy.

2012:

After a promising set-up (at least promising for a needless sequel) with the

death of Renee and Jeff’s arrival in Ludlow, “Pet Sematary II” takes a sharp

turn into pure nonsense. It’s hard to believe Lambert directed both films, as

the sequel is such an inept, confusing, pitiful creation, coming nowhere near the

full scale haunt of the original picture. This “II” or “Two” or “2” (depending

on your info source) is laughably bad, almost worth a recommendation to

cinephiles on the prowl for a sequel that’s a polar opposite viewing experience

than its predecessor, at times almost relishing its waywardness. “Pet Sematary

II” looks like a feature that quickly slipped out of Lambert’s control, and she

decided to drive the production into the ground out of spite.

While

the process of sequelizing King without King’s participation is a daunting

prospect, the script (credited to Richard Outten) doesn’t make much of an

effort to summon a similar claustrophobic tone of insanity. With the powers of

the burial ground established, Lambert introduces more of a darkly comic tone

to the follow-up (frosted with a score straight out of a Vivid Video title),

with Gus’s mid-movie undead rampage played largely for laughs…I think. It’s difficult to tell what the

movie has in mind during any given scene, with the writing and direction in

separate corners, refusing to speak to each other. Attempting to build on the reanimation

concept, “Pet Sematary II” takes the gore show routine, robbing the picture of

interesting characters and a general taste of delusion. Instead, we’re stuck

with dopey kids in way over their head, yet they fail to acknowledge their

troubles with any sort of recognizable facial reaction or genuine human

impulse.

The

acting is atrocious in the feature, with pros like Edwards surviving to the

best of his ability despite projecting looks of concern for his career, while

Brown doesn’t know how to play anything with a degree of subtlety, wearing Fred

Gwynne’s Maine accent from the first film like an iron sweater. In the lead

roles, Furlong and McGuire (who lasted for two more movies before ditching

acting altogether) are too drowsy to matter, glumly going about their business

when scenes require a generous helping of disbelief, or at least mild

curiosity. A parade of undead creatures is treated with all the excitement of a

bible reading by these two, with Furlong especially flimsy as the O.G. John

Connor moved forward on his unlikely acting career.

Previous

complaints about violence are confirmed with a second viewing. Aggressive is

the treatment of animals, arguably a crucial component of the plot, yet handled

exploitively by Lambert, who teeters on the edge of relishing the opportunity

to use sights of dead kittens, skinned rabbits, and wounded dogs to provoke the

viewer. It’s not a parade of slaughter that would be allowed in contemporary

cinema, solidifying the feature’s 1992 origin. Better is the monster make-up,

though most of it is neutered by MPAA tampering, attempting to soften a

surprisingly hostile effort. Even the bullying antics with Clyde seem

overheated and silly, creating obvious enemies to pad out the thin story,

killing time before someone finally gets around to digging up Renee’s body for

the burial ground day spa treatment. That’s what everyone is waiting for, yet

the production seems reluctant to indulge the wish right away. After all,

there’s a perfectly boring story to tend to and amateurish directorial

flourishes to digest before anything of substance can commence.

To

close out the film with a real head-scratcher, Lambert elects to “honor” the

dead by reminding the audience of those who perished during the feature,

rolling through footage of the characters before the end credits hit awkwardly.

It’s a bizarre artistic choice that almost needs to be seen to be believed. In

fact, here it is (in an indeterminate language):

Wow. If ever there was a feature that cried out for a

director’s commentary, it’s this one. Lambert really needs to sit down and

share the particulars of her headspace during the creation of the movie. “Pet

Sematary II” is begging for such an

inspection.

Leave a comment